“Hi ladies how are we doing this evening can I get you started with a drink?”

My mother and I looked at each other across the table, unsure of how to respond, or even who should respond. This sweet waitress was just trying to do her job — it’s hard work acting chipper in the soul-crushing environment of a suburban Applebee’s — but her canned greeting had lit a powder keg and an eruption of embarrassment now hung in the air. I finally piped up in my awkward contralto voice: “I’m a boy.”

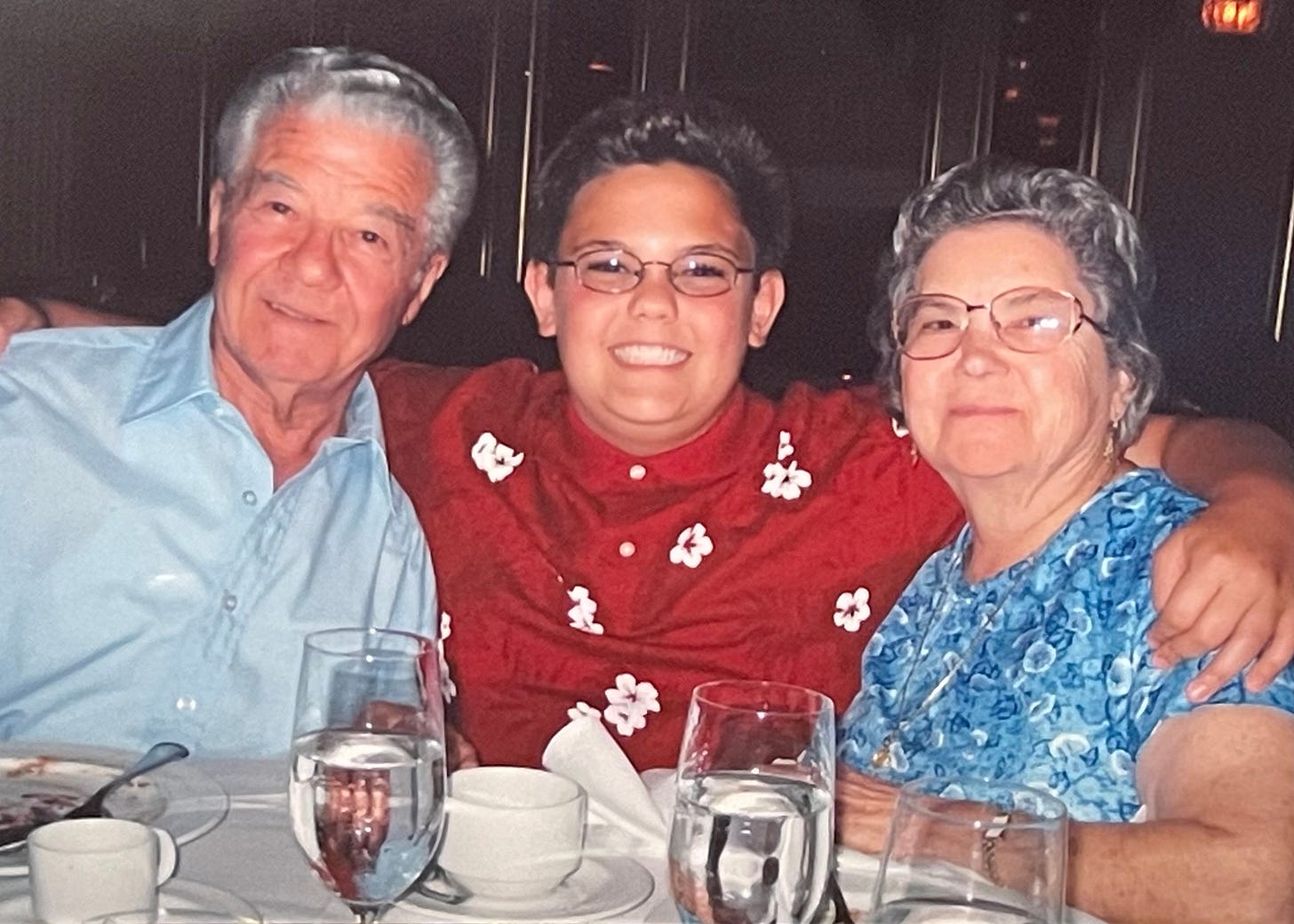

This was my first encounter with being misgendered, but certainly not my last. As I entered my teen years I left behind my discernible boyhood and entered a period of inscrutable androgyny. While everyone else’s voice was dropping, mine remained relatively high-pitched. In a drastic departure from my childhood buzzcut I grew my hair out to the point that it covered my ears. Combined with my perennially round face and luxuriously long eyelashes I looked like Rosie O’Donnell circa 2003.

But most importantly I had gotten fat, or really, fatter. I was no longer the combination of cute and chubby that I had flirted with throughout elementary school. Instead of the baby fat melting away it had simply solidified and expanded into fat fat, something less cute and more morbid. Suddenly the medicalized language of “obesity” was being thrown around as my size became a common fact about me that everyone felt they could speak on.

The weight collected most in my chest and hips, feminizing my body and transforming it into an object of ridicule from my peers. The boys loved my tits, in their own way: a friend of mine once mockingly and repeated squeezed my breast so hard that his fingers left tiny bruises all across my chest. I hated this attention and I attempted to hide from it by dressing myself in the least restrictive garments I could, enormous t-shirts and sweatpants that hid any impression of shape. I’m sure I was wearing something similar that night at Applebee’s; draped in such an ensemble it’s perhaps no wonder that our waiter thought I was a girl.

It’s not like I didn’t know I was fat. The only reason we went to Applebee’s in the first place was to sample their new Weight Watchers menu.1 A potent combination of self-loathing, teen bullying, and casual familial fatphobia had convinced me that I needed to go on a diet. My mom was starting up with Weight Watchers again herself so I glommed on, learning the tenets and rituals of the “lifestyle.”2 I never attended any meetings, never had to have fluctuations in my weight announced before a room of strangers, but I was otherwise a devout point counter.

Weight Watchers has toyed around with its diet since its inception, but the basics of the gimmick have remained the same for the last twenty-five years.3 Rather than counting calories, dieters are given a daily allotment of “points,” which is determined by your weight, height, age and gender. Throughout the day you “spend” these points on food, which each have a cost derived from their “nutritional value.”4 Foods that are low in carbs or fat, or high in fiber or protein, only set you back a few points, whereas richer dishes are more expensive. The goal is to budget your points throughout the day so as to get the most bang for your buck, to feel the most full without going over your limit.

The points system has proven popular because it emphasizes choice and flexibility. Nothing is off limits on the Weight Watchers diet, no one’s telling you what you can and can’t eat. Planning to skip breakfast and lunch so you can go to Panera for dinner? No problem! Need a glass of red wine with dinner? You go girl. Do you love bread? Eat bread every day! Each dieter gets to feel like they’re in control of what they’re eating, as if meticulously managing your daily points is a practice in autonomy.

In reality Weight Watchers doesn’t care what you’re eating, or if you even like what you’re eating. The points system turns food into a number, abstracting it even further from its caloric total or macronutrients. Those easy, single-digit numbers gamify the entire process of eating, with the promise of thinness as the prize at the end.

At thirteen I easily memorized the rules to this game and found myself surprisingly good at it. I grew to be a wiz on the PointsFinder slide ruler and became fluent in the Complete Food Companion and the Dining Out Companion.5 I had yet to develop a mature palate so settling for bland Smart Ones frozen meals or dry Weight Watchers-branded snack cakes didn’t feel like deprivation. I was praised for how “good” I was when I would skip dessert during a dinner out with my family. It all tasted like winning to me.

I did end up losing a fair amount of weight near the end of eighth grade, but I don’t think it had anything to do with my dieting. A growth spurt, combined with the anxiety that came from my grandmother’s illness and eventual death, leaned me out a bit before I headed into high school. I was still a big kid, but I was no longer quite fat enough for it to be the only thing people noticed about me, close enough to thinness that I could once again disappear into the crowd.

That was the hardest thing about being a fat teen: it outed me. My body made me stand out during those cruel middle school years when homogeneity is most in vogue. I had worked hard to stifle the flamboyance and omnidirectional affection that were my trademarks as a child, but my size could not be hidden.6 My tits and hips externalized an inchoate queerness that was brewing inside me. I wasn’t yet gay, but my fatness marked me as un-masculine, a Friend of Dorothy in the making.

Perhaps the reason I was so good at following the Weight Watchers diet is precisely because I was so good at keeping myself in the closet. A similar logic underpins both practices: with so much focus on calculation and moderation there’s little room for spontaneity and joy. I policed my daily points and my gay thoughts with equal vigor: a moment on the lips a lifetime on the hips, and let’s make sure those hips don’t swish! If I could just control both of my worst impulses I would end up straight and skinny. What more could I want from life?

This interconnection between my sexuality and my body image has — surprise! — led to lots of dysmorphia throughout my life, especially as I grew more comfortable in my queerness. I never again dieted with the same rigor as when I was on Weight Watchers but I tracked my calories on MyFitnessPal for years as an adult. I was always desperate to lose more weight. Even at my absolute thinnest in college I still thought I was too big to be desirable to other gay men; I ignored my gaunt face and could only obsess with how “huge” my love handles looked. Who would want to fuck someone like that? I went from being too fat to be straight to being too fat to be gay.

It’s only in the last few years that I’ve begun to seriously tackle the loathing that still lingers from being a fat closeted teen. I’m lucky to be living in an historical moment in which fatness, or at least a certain kind of fatness, is hot and fatphobia is not.7 Bolstered by this sea change I’ve worked towards a new relationship with my body and food. I’ve focused on what feels good and what tastes good and denied myself nothing. I’ve taken up cycling and yoga and weight lifting (not all at once) and eaten fresh in-season produce and pints of Häagen-Dazs and pasta by the pound (sometimes in the same day). I suppose that’s part of why I consider this my Nonna era: I’ve finally reached a point where I’ve let go of quantifying sustenance and pleasure and instead started to embrace abundance. I simply say yes to more.

And yes, I gained a bunch of weight — coincidentally I now wear the same size clothes I did when I was thirteen — but about a year ago my weight plateaued.8 Now, no matter how much or how little I eat, no matter how much or how little I exercise, my body remains in the same five-pound range. A body’s refusal to budge can drive a dieter crazy, but I take enormous satisfaction in it. My body’s telling me that it’s at home at this size, which inspires me to find comfort in it as well.

It’s a work-in-progress. I still occasionally inspect photos of myself taken by others and think “I look so fat.” But as Lizzo herself reminds us not every thought needs to be a positive one, even as we work towards a more positive sense of self. Nothing can stop me now. I’m just hoping that by next summer I’ll finally be ready to really rock a crop-top.

This partnership began in 2004 and continued until 2012 (at least based on what I can find). What this partnership essentially meant is that Applebee’s could advertise using the Weight Watchers name and could explicitly list how many “points” certain items on the menu cost.

Many of my friends testified to a similar experience of being a fat teen with fat parents and going on Weight Watchers together. In recent years, the company has worked to expand its market younger and younger. In 2018 they made the program free to teenagers between the ages of 13 and 17. Horrifically, in 2019 they introduced “Kurbo,” an app which helped children as young as seven track their daily nutrition and manage their weight loss. You can read Aubrey Gordon’s response to this news here, in which she highlights the many dangers that can emerge from childhood dieting.

The “point system” was first introduced in 1998, but has undergone many small shifts throughout the decades. Weight Watchers has “innovated” or “reimagined” its points system seven times since its inception: in 2000, 2002, 2004 (around the time I was dieting), 2010, 2016, 2018, and 2022.

This economic language of “spending” points and “budgeting” them is pulled right from the company’s website.

These companion books provided shortcuts for calculating points for meals you were making at home or eating out at chain restaurants.

I didn’t see anything wrong with wanting to kiss both boys and girls until someone told me it was wrong.

Of course, this celebration of and support for fat bodies is not evenly distributed: fatness intersects with race, class, gender, and sexuality along both existing and novel lines of discrimination.

I’m still what would be considered a “small fat,” insofar as folks of my size “have the most privilege of the fat spectrum and do not typically have trouble with size-based accessibility.

I love you no matter what size you are!!! You were a junior member of the I.F.B.A. and now you are a senior member... maybe one day you can become president like me!