In one of the few memories I have of my Nonna, she’s teaching me how to make lasagna. The ingredients sit arranged on the small formica kitchen table that I never once saw without its thick sheet of plastic covering. She starts with a ladleful of tomato sauce, swirled with the back of a spoon into every corner of a glass baking dish to make sure nothing gets stuck to the bottom. Next comes a layer of noodles, followed by ricotta,1 ground beef, more sauce, mozzarella, and parmesan. These layers2 repeat and build on each other until we reach the lip of the baking dish, which she then covers in aluminum foil and pops in the oven. She tells me you have to wait for it to bubble around the edges, at which point you can remove the foil and let the top brown for a few minutes. Then you take it out, let it rest,3 cut it up, and enjoy.

No matter what Stouffer’s might try to tell you, lasagna is a dish reserved for special occasions, something you spend the time to make once a year to feed a crowd. In my family it’s part of our (effectively secular) Easter celebration, served as an appetizer at dinner before the main course of lamb and mint jelly.4 This co-starring role used to be filled by my maternal grandfather’s Easter orzo, but that changed after my Nonna passed away in 2006. Since then, the lasagna’s presence marks her absence, memorializing what has been enshrined in our collective memory as her last meal.

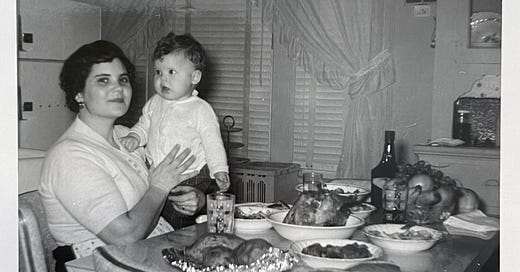

In the autumn of 2005 my grandmother was diagnosed with a particularly aggressive form of brain cancer that was undaunted by a winter’s worth of surgery and radiation treatment. By the spring she had entered a palliative care facility where the main focus was on finding ways to maintain her quality of life. That Easter we5 prepared a lasagna and Sunday sauce — complete with meatballs, sausage, and spare ribs — using the recipes that my father had translated and transcribed from her. I remember she smiled (I think) after her first bite, which I took to mean that it tasted good, or at the very least that it tasted decent enough that she was happy with the result. Because her final month was marked by such a precipitous decline in which she slowly lost her appetite and then finally stopped eating all together, this Easter feast came to signify a final moment of gustatory joy.

After my Nonna was gone we decided to repeat this lasagna ritual every Easter to celebrate her life and memory. Having learned how to make it from her firsthand, I was the designated lasagna maker. Every year my latest attempt is met with a chorus of acclaim as my small-but-loud family assures me of how delicious it is, how it reminds everyone of Ida’s cooking. Yet every year all I can do is fixate on my lasagna’s shortcomings in comparison to my memory of what hers tasted like. Mine is always too dry, or the balance of sauce to cheese isn’t quite right, or there weren’t enough eggs in the ricotta to keep it from falling apart when you cut it.

I suppose I’m not really disappointed by the lasagna; I’m disappointed by my inability to fill my Nonna’s shoes. My father (bless him) does not cook, and my mother (bless her) can cook but doesn’t like to. The cooking gene, it seems, skipped a generation, and so I became the inheritor of the “Corbo Cuoco” title.6 And while cooking did, and still does, bring me immense joy, I can also see what a heavy title it was for a fourteen-year-old to take on. In trying to continue my Nonna’s legacy, to cook how she cooked, what was intended as commemoration ended up feeling like replication, to remake what no longer was. Having lost my first grandparent, I tasked myself with the job of bringing her back to life the only way I knew how: through her food.

But, of course, there is no way I can cook like she did. For her entire life, my Nonna spent every week rotating through the same dozen-or-so recipes that she came to know by heart. Habit had transformed cooking into something second nature for her. There were no measuring cups in her kitchen, just handfuls and pinches. Cooking times and temperatures were determined by smell and look and taste. Looking back at the few recipes she passed on, it’s plain to see that they aren’t so much recipes as they are a list of ingredients. I don’t think she could have communicated to me the full nuance of what it meant for her to cook even if she tried.

I used to bemoan what felt like an incomplete passing on of knowledge, a lost trove of mastery that died with my Nonna. But increasingly I’ve come to see these gaps as gifts, permission to build on what she taught me. Don’t get me wrong, I can’t cook with the same consistency as she did, so my culinary education won’t be the same as hers, but how could it be? Instead I’m trying to build my own unique habits, rituals, and flavors as I try to embody all things Nonna. And while I can’t resurrect her through my cooking, I can instead channel her spirit into something new, something that is distinctly mine.

Many cooks, including Marcella Hazan and Samin Nosrat, use a béchamel sauce in their lasagna instead of ricotta. This Washington Post article from 2000 suggests that the shift over to ricotta could have been part of an “Americanization” of lasagna.

There’s no “right” way to layer your lasagna. While Nonna put every ingredient in every layer, Lidia Bastianich and Carla Lalli Music separate ingredients by layers in their lasagne.

I cannot overstate how important it is to LET YOUR LASAGNA REST otherwise you’ll end up with a molten mess.

Truly, mint jelly is up there as one of the most atrocious foods ever created.

Shout out to Susan Corbo, my ever-trusty sous chef, and Manny Corbo, taster-in-chief.

Worried about my consumption of cartoons as a child, my parents told me that I could watch the Food Network without restrictions, so my best friends growing up were Ina Garten, Rachael Ray, and Sandra Lee.

Always so reassuring to see the other Food Network childhood girlies out there. <3