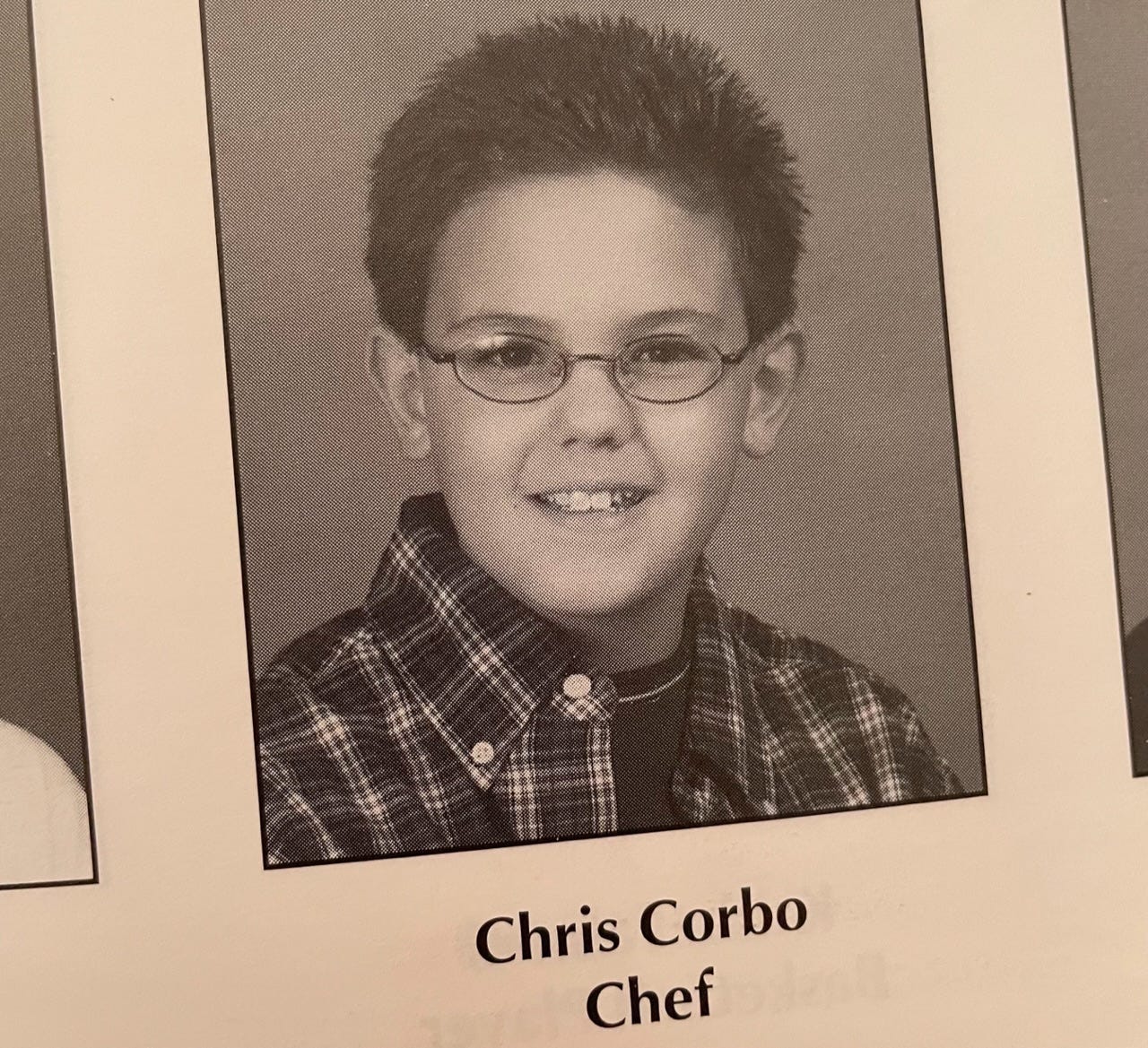

The 2001/2002 school year was marked by two tragedies for fourth grader Chris Corbo. First, the terrorist attacks on September 11. Second, the fact that he didn’t get into his elementary school’s gifted and talented program. As Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson reminds us, “Different things can be sad.”

9/11 took place on a beautiful Tuesday morning the week after Labor Day. Everybody writes about what a beautiful morning it was in New York that day; it was just as beautiful in the Jersey suburbs where I grew up. At Anna C. Scott Elementary first period passed without incident, but by second period students were being called down to the office one after another in a steady stream. They were told to bring their things, as they’d be leaving for the day.

By the time I was beginning to grow suspicious my name was the next to be called. For all I knew was that I was about to have the day off, so I skipped down to the main office to find my mother waiting for me. She explained, calmly, that we were going home because somebody had bombed the World Trade Center in the city.1 I didn’t know what the World Trade Center was — I imagined a large, squat office building — but I understood that a “bombing” was bad. As we drove, my mom told me not to turn the TV on when we got home: she didn’t want me to watch the endless loop of the towers being hit and going down. I’m sure at some point we all watched this footage as a family, but I have no memory of that. I only remember waking up the next morning before my parents and watching it alone in the living room.2

The following months were filled with memorial services and telethons and Lee Greenwood singing “God Bless the USA.” As my community was grieving, I felt largely untouched by the attacks. My family, friends, and my friends’ families were all safe, as far as I knew.3 For nine-year-old me it seemed like the worst thing to come from 9/11 was my parents’ decision not to fly to Disney World to celebrate my 10th birthday.4

The full impact of that day slowly unfolded over the following months just beyond the edges of consciousness. The unexpected had always been a trigger for my anxiety, but new scenarios and stimuli soon became intolerable to me. I suddenly grew afraid of thunderstorms after having spent years watching them with wonder; I was scared of going to the movies because I got too anxious waiting for the previews to be over. I hated being in any situation where I did not, or could not, know when something might (or might not) happen. I craved order, control, predictability. Put another way, I hated any scenario that reminded me of the inevitable reality of the human condition: that one day we will die, but we can never know exactly when.

These new fears were all easily written off as the idiosyncrasies of an anxious kid. It wasn’t until I was rejected from the school’s gifted and talented program later in the school year that it became evident that I wasn’t just an anxious kid, I was a kid with anxiety.

It wasn’t so much the rejection that led me into a mental health spiral, it was the sheer waiting for an answer. Every day after school for weeks I asked my mom if she had heard anything about the program, and every day she responded that she hadn’t. I longed to be recognized as “gifted,” to be anointed into an elite echelon of students who had the privilege of skipping class once a week to share their talents with each other. Instead, I found myself in perpetual anticipation of an answer that never seemed to be coming. I was numb by the time I finally got the news that I hadn’t been admitted to the program, already inconsolable before the disappointment had even arrived. The numbness my father has described feeling on the morning of 9/11 eventually hit me as well, it seems, it just took months for it to happen.

Soon after getting the news I spent the weekend with my aunt, uncle, and cousin while my folks were out of town. Weekend sleepovers with my aunt and uncle typically promised a glorious cavalcade of things that were off-limits at home — sugary treats, cable TV, my cousin’s Barbies — but instead I spent the weekend cocooned in a blanket on the couch, disinterestedly playing Pikmin on my Nintendo GameCube. I felt nothing, I just wasn’t sure how to describe the nothingness that I was feeling.5

The only thing I remember eating that whole weekend was the box of Cap’n Crunch Oops! All Berries cereal that my aunt had gotten me in an attempt to cheer me up. Like Nonno, she knew the wonders sugar could do for my mood. I ate the entire box hoping that, eventually, I would feel better, but my mood refused to improve. Instead, the anxiety-induced gastrointestinal distress I experienced all weekend quickly transformed the cereal into a tie-dye mess in the toilet bowl.

Beyond the traumas both geo-political and personal, I think what I remember most about this string of events is that it marked the first time in my life that food failed to provide comfort. To echo a sentiment expressed by my friend Caleb a few weeks ago, it felt as if food had lost some of its inherent magic. Whether homemade or prepackaged, it no longer seemed to offer the same capacity for emotional revival.

Curious, then, that it was right around this time that my younger self began dreaming about becoming a chef one day. I used to simply chalk this as a side affect of all the Food Network I watched once my family finally got cable, but I wonder if this goal was instead an attempt to reconnect with food in a new way. Rather than being simply on the receiving end of a meal, what might it look like to also create such dishes? Cooking became the comfort, not the food; food remained comforting, but it was the process that grew to be a practice in self-care.

There’s something very proto-Nonna about this behavior, I think. I remind myself that Tomie dePaola’s Strega Nona takes care of her community, but she cooks for herself. I cook for myself even when I share the meal with others. It’s not a labor I would undertake if it didn’t fill my cup up most of all.

If you made it this far, thank you, and thanks for coming to visit My Nonna Era! If you enjoyed this essay and want to support my writing, please share it on social media and tell your friends to subscribe.

Comparatively, I’m lucky that I didn’t find out about the attacks at school. I did an informal poll of my Instagram followers this week, and a huge swath of millennial respondents said they watched everything unfold on TV at school. I can’t imagine anything more horrifying.

The antenna on the top of the north tower was used to broadcast all TV channels in the NYC area. Since my parents didn’t have cable, we lost almost all of TV access when the towers collapsed. One or two channels survived — I wish I could remember which — so those days were mostly spent watching videos on VHS to pass the time; after I had had enough of the footage on the morning of September 12 I put on Grease.

Years later my mother’s best friend since childhood recounted her experience on that day to me. Not everyone had been as unaffected as I had thought.

My 10th birthday coincided with Walt Disney’s 100th birthday, which only added to the symbolism of it all.

I’ve never received a formal diagnosis for depression, but I’m pretty sure we could describe what I experienced here as a depressive episode.