Company's Coming! with Guest Nonna Spencer Alcorn

Pleasure, Seriously: On dads, receipts, and haute cuisine

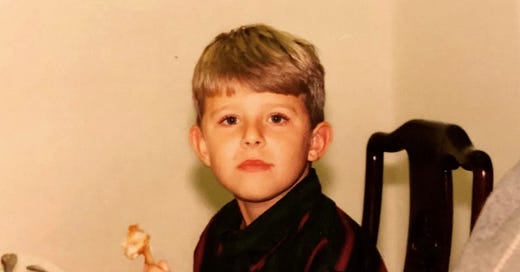

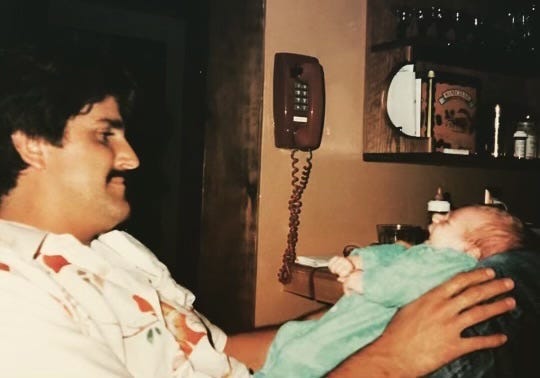

In considering kitchen ephemera to spotlight for this piece, it became immediately clear that any sentimental culinarily journeys were going to center on my late father, an accomplished cook and gourmand (he’d skin me for calling him that, or “foodie,” though both are accurate — he resisted being perceived on anything other than his own preferred terms).

Maybe I’d write about some of the superb meals I’ve made over the years in the cast iron Dutch oven he gave me as a housewarming present in my first-ever solo apartment. Or maybe I could write about the menus and recipes I have from the cooking classes (actually more of a demonstration lunch) at Mille Fleurs, a restaurant near where I grew up in north San Diego County. These classes were favored gifts for my father in the middle and later 1990s, and their menus are very much of the era (Dungeness crab cakes with white corn and red bell pepper sauce, multicolor beet and potato salad with smoked eel and horseradish). Maybe I’d write about the Wusthof knives he bought for culinary school (at the now-defunct California Culinary Academy, also near San Diego), from which he graduated in 1999. When we rented houses on trips, he traveled with those knives, never suffering the indignity of inferior knife blocks. I have them now, and use them on special occasions, restraining myself so as not to be more precious about knives than I already am.1

Something I probably wouldn’t write about, I thought, was the heap of receipts and menus from meals around the world through the years (it’s about an inch thick, which is a lot of receipts but not storage-unit or even bankers-box size). We ate very well at home, but in traveling, my father relentlessly pursued the local best. My father’s highest praise from my father was “correct,” offered as an assessment when a meal, or dish, or drink, met his approval; this collection represents years of various correct meals.2 (My mother’s highest praise, similarly, is “appropriate.” This only child’s been in therapy for ten years and counting.)

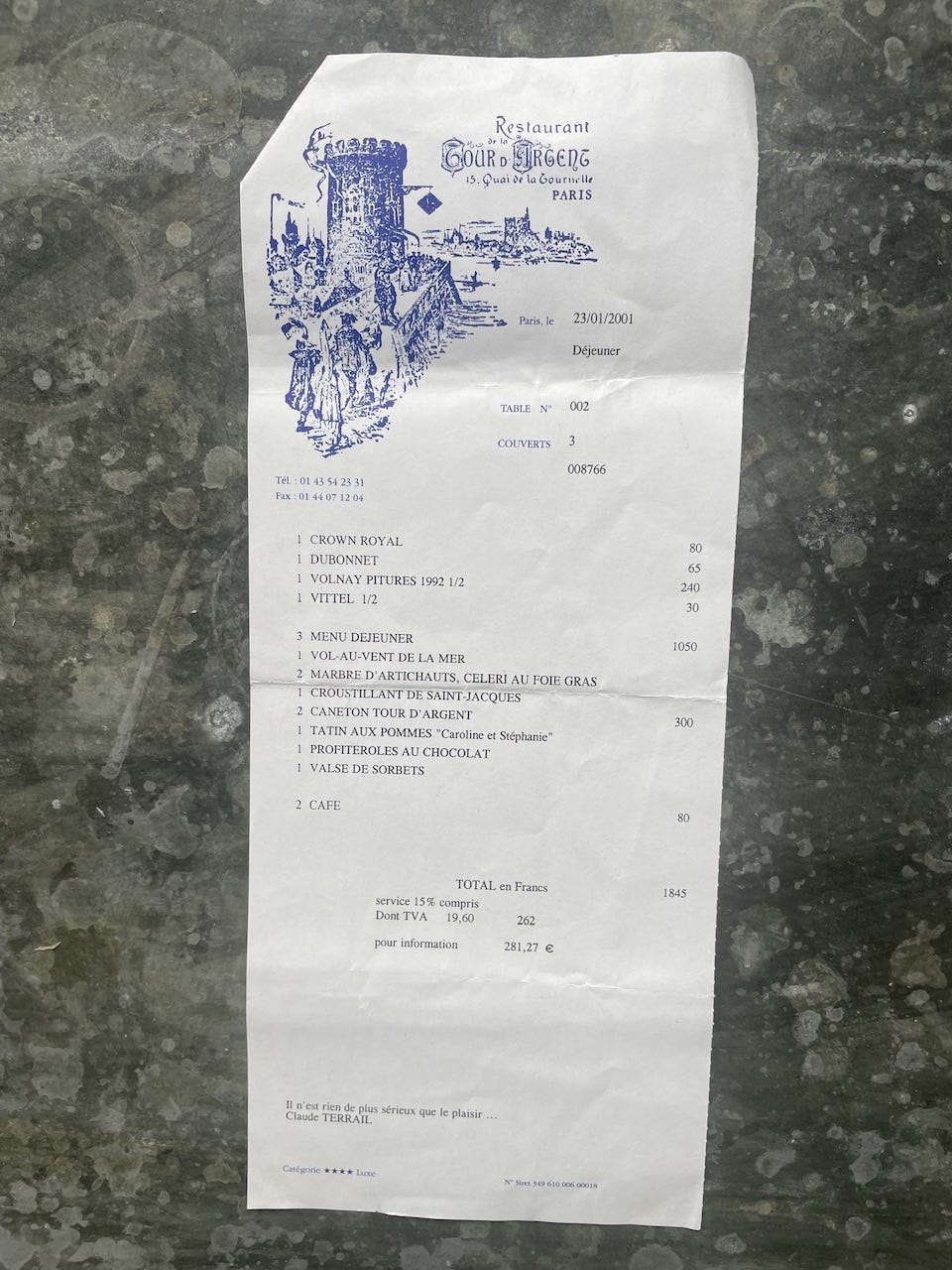

“Il n’est rien de plus sérieux que le plaisir.” That’s French, for starters,3 and it’s also a quote that’s sometimes attributed to the poet Jean Cocteau. On the bill for a January 2001 lunch at La Tour d’Argent in Paris, it’s attributed to that restaurant’s proprietor, Claude Terrail.4 I remember that lunch, or the contours of it, one in a real motherfucking banger of a five-day stay in the French capital — consecutive lunches at, in order, Le Grand Vefour, La Tour d’Argent, Lucas Carton, Taillevent and Le Jules Verne, and no, I don’t know how we didn’t all get gout, though that list is pretty de bon goût for its own time and place.5

Lunches only? Yes: after a 1998 San Francisco trip went awry — a one-two punch of a four-and-a-half-hour dinner at Campton Place, where long service pauses left all three of us increasingly volcanically frustrated, followed the next day by an eight- or ten-course tasting menu at Masa, which he experienced course by course in reverse order into the toilet later that evening — we didn’t do big dinners out when we traveled. Lunches only, and incidental sketchy snacky dinners out of minibars or hotel lounges. Girl dinner, avant la lettre.

So – that lunch. La Tour d’Argent is well-regarded, a little long in the tooth even then, certainly very old-school and certainly very correct. Duck was the move, their signature dish, and one which they’ve numbered since 1890. On this trip, I had duck #926,291. The Crown Royal on the bill would have been my father, the Dubonnet (ordered “over and with a twist,” I’m sure) my mother. I remember I got a glass of the 1992 Volnay Pitures, which was exciting (at sixteen years old). At the bottom of the receipt, that quote: “Il n’est rien de plus sérieux que le plaisir.” There is nothing more serious than pleasure.

Quippy, sure, but an interesting idea and one that resonates, given my own (inherited from dad, perhaps, like the knives) tendency towards gravity, solemnity, not quite depression but what the French (when in Paris) call le cafard, the same contemplative anxious-melancholy tendency that led my mother to ban my father from reading Russian literature and Emily Dickinson from September to April. My father wasn’t sentimental, per se, or overtly, but had a deep sensitivity that was often at odds with the world’s expectations for him. He succeeded on its material terms, but quested, I think, for satisfaction.

His approach to restaurants and cooking was nominally driven by pleasure, but pursued with professional vigor and acumen. I have no doubt that he enjoyed the cooking classes at Mille Fleurs I mentioned, but he also approached them as instruction. The pages themselves document, through scribbled marginalia, an increasingly developed skill set. In 1996, he’s noting that quail breasts and legs should be cooked separately. For oeufs à la neige, in May 1998, he’s noting that the egg whites for the meringue should be started at room temp. Later that year, a packet entirely without notes. Another in ‘99. He was getting better.

He wanted to know exactly what to do, where to go, exactly what to order when he got there, and who to trust for a wine pairing. It’s a fervency I can sometimes recognize in the way I overdo things — why not drive faster, why delay gratification, why enjoy the ride if the point’s at the end?

This was also, at the end, how he approached death, which was not intentional but was pretty brilliantly ironic. Glioblastoma multiforme took him out in a matter of weeks post-diagnosis. The gallows humor about my father never doing anything slowly or by half-measures came directly on the diagnosis’s heels.

I wish someone had told me this, so now I’m telling you: you’ve got to be very very careful what you hand-feed a dying loved one in the hospital because you’re going to be off that food for the foreseeable (in this case, romaine with a creamy Caesar dressing, braised short ribs, and molten chocolate cake).

The salad and the cake are not great losses, but there is a short rib recipe that we loved at Daniel on trips to New York City; the recipe is ludicrously expansive in terms of time and ingredients and among the few I have ever made where the quality of the wine used (three bottles, if you please) has a meaningful effect on the finished product. It’s representative of the process-focused long braises that my father loved, the daubes and stews and bourguignons that start early in the afternoon and build momentum as they’re endlessly tended; he never seemed to have much appetite for their final product, noting that he’d been sampling it all day.

He was also the first and harshest to critique his own work, another inherited habit, or maybe that same inherited habit: if it’s pleasure you’re seeking, take it seriously, and know how to get there efficiently and effectively. Be relentless in process improvements. Too much salt. Pull the bouquet garni earlier. This pancetta didn’t quite render. It’s been the work of a lifetime to get that voice in my own head to be helpful and encouraging, rather than cruelly critical, and to realize that the pleasure, here in the kitchen, can be in gentle exploration and experimentation, rather than fabulous and extravagant success.

My father also loved grand presentational abundance: crown roasts and whole fish and prime rib, the last of which we had at Thanksgiving instead of turkey. When I worked at the Sundance Institute, Thanksgivings were at the height of my busy season. I couldn’t travel, and rather than subject my friends to the angst of being enormously stressed by undiscussable work (NDA, babes), I would Uber to Lawry’s on La Cienega, solo with a novel, for a big drink and a prime rib dinner for one, surrounded by chattering families and those big chrome carving carts. There. Pleasure, taken seriously, and approached methodically. A known formula, with known results.

I wrote earlier about hospital food. Food in hospice is something you’ll still remember, but there’s so much other bad shit going on that you’re a little desensitized to it. It’s also unhinged when you’re dealing with a terminally ill neuroncologoical patient in the hospice stage who’s been getting everything he’s supposed to want for the last 66 years; some wild-ass combinations at weird hours, like margaritas and macaroni and cheese for lunch. I made that macaroni and cheese, and put about sixty dollars worth of five kinds of cheese into it. (Fervently overdoing it. Taking it seriously. Every interaction at grocery stores in those weeks had the affect of Julianne Moore’s monologues in Magnolia, which was an exhausting and camp way to live, I remember fucking daring the cashier to say anything about my cheeses.) I don’t even remember how it tasted, but I’m positive a couple of the cheeses overwhelmed at least one of the others, I probably scorched the bechamel, again, overdoing it in some frantic bid to, you know, cure brain cancer with cheese.

After the first bite, my father paused, chewing, looking into the middle distance, and asked — “do I detect Gruyère?” I nodded wordlessly.6 He closed his eyes, and gave a brief nod — correct, to and at the end.

Spencer Alcorn is a communications executive who lives in Los Angeles, California. His dog has the same name as his partner’s mother, which everyone involved has mixed feelings about.

*dabs tears with tissue* wow mac and cheese will never be the same again. Anyways, thank you for reading this edition of Company’s Coming! If you enjoyed Spencer’s essay, please share this post and encourage folks to subscribe to My Nonna Era!

When I was in early days of dating my now-partner, I remember complimenting the sharpness of a knife as I cooked in his kitchen. With enormous sternness, he said “Nothing’s more dangerous than a dull knife. Nothing.” That’s a metaphor for another Nonna!

The correct restaurants were not the most interesting — Anthony Bourdain and Jonathan Gold, who died within striking distance of my father in that brutal summer of 2018, would complicate the concept of “best” beyond finest-dining, but one did what one could in those days.

Well, French for starters is actually “hors d’oeuvres,” just to get that straight.

Unrelated, but for the fact that the quote has also been attributed elsewhere: “whoever said money can’t buy happiness didn’t know where to shop” is frequently attributed to Gertrude Stein, likely because of a format-related misattribution examined here. Shoutout to my dear friend Nick for pointing out that, and many other inherently ridiculous things.

And no, we didn’t know how late in the empire we were.

Those who have stood at the bedside of someone who is dying know that there is a tendency to burst into tears instead of answering a simple question; I remember thinking that felt very distressing to the patient and was trying to restrain myself.