Cultural Indigestion

There’s an ingredient I like to always keep in the cupboard, whether in a more authentic form or even the Trader Joe’s version (I know, sorry Mom!!), and regardless of how often I actually use it. That is the spice za’atar — or rather, it’s really a mixture of spices that include the spice za’atar along with toasted sesame seeds, dried sumac, and some salt. Different regions may use slightly different ingredients based on what’s available locally, but that’s the gist of it. It’s an ingredient that has been used in a lot of my Mom’s cooking, most commonly on her homemade hummus1 which is a regular dish at almost every family gathering: birthdays, Jewish holidays, non-Jewish holidays, you name it, Mom’s hummus2 is on the table, and it is always topped with za’atar. Just the smell of za’atar brings a nostalgic feeling of home — and herein lies my cultural indigestion — something so delicious and important to me that hasn’t been sitting quite right with me.

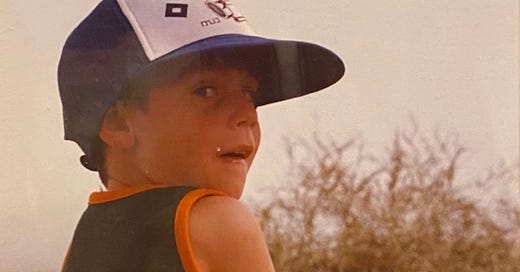

At an early age, my mom and her family left California, where she and her three younger siblings were born, and moved to Israel (or as it is referred to in Judaism, they made ‘aliyah’). Mom and her family then grew up there on an Israeli agriculture settlement called a kibbutz — actually a few over the years — and eventually joined the Israeli army as all 18 year olds do after high school. My dad, on the other hand, born and raised in San Francisco, first experienced Israel through the confirmation class trip to the country, which was and still is a very typical trip for 10th graders to take with their Hebrew School class at most US synagogues. He then went again the following year, and in his late 20s, he made the decision to move to Israel as part of an immersion program where you work and live on a kibbutz and learn the language and way of life. It just so happened that Dad joined the program (called an “ulpan”) on Mom’s kibbutz, and that’s where they eventually got married. They moved back to the Bay Area and had me and my three siblings, but after my youngest brother was born and I finished kindergarten, we moved to the same kibbutz where my maternal grandparents still lived and we lived there for three years before moving back to the Bay Area permanently.

During my time in Israel, foods like hummus, falafel, schnitzel, and borekas, and flavors like za’atar, alongside many other Eastern European-influenced cuisines, became a huge part of my diet and way of life. I can still picture (and smell) the blend of goulash next to borekas next to schnitzel in the cafeteria-style serving line at the communal dining hall on the kibbutz. I also remember learning to make pita from scratch on homemade ovens, which was always seasoned with fresh za’atar, along with my fellow classmates in the children's house. Just writing this I can smell the mix of toasting pita dough and the za’atar crisping on top of it. Makes me all fuzzy inside.3

Za’atar smells like home, but its origins are from someone else’s home. For the past several years, I’ve spent a lot of time working to unlearn some of the Zionist ideals that have been ingrained in me since essentially birth, particularly the idea that Israel is always a home I can return to — that no matter what, it’s my right as a Jew. While I do often miss Israel for nostalgic reasons and because I miss my Savta (Hebrew for Nonna) who still lives there, one of the things I miss most is “Israeli food”. When you think about the fact that most Israeli Jews immigrated to present-day Israel at some point in their lineage, and you think about the fact that many of those were migrating from eastern Europe, it really starts to make you question whether dishes like hummus and falafel, and spices like (you guessed it!) za’atar were something that they brought over with them.

Well spoiler – they weren’t. Those foods were already local in Palestine. Of course, there are other elements of “Israeli food” that did come from the Jewish migration to the area that have been infused into the local Palestinian (and, more broadly, Arab) cuisine like schnitzel from eastern Europe and shakshuka from North Africa. Moreover there are Mizrahi Jews who came from North Africa, Iraq, and Yemen where similar foods are also eaten, and who brought with them burekas and kebabs, all of which often fall under “Israeli food”. But all research has found that these foods did not come from those regions.

At what point is food being assimilated and blended versus being appropriated? Sometimes the line can be thin, but it’s hard to argue that when the people who originated the food you’re now claiming have also been forced out of their homes to make room for more immigrants who lay claim to the land.

When my husband and I got married, we decided to serve food representative of both of our backgrounds; we ordered food from a local Filipino restaurant because he is Filipino-American, and we ordered food from a local Israeli restaurant because… I grew up with it and it’s meaningful to me. If you walk into any restaurant labeled “Middle Eastern food” and talk to the owners, you’ll often find out they are Palestinian, or sometimes Lebanese, Jordanian, or from another Arab country in the region. However, we ordered from an Israeli restaurant, kosher and all. I enjoyed being able to share this food with my new in-laws and family members as well as friends, though at the same time I felt conflicted through the process and found myself hesitant to say “we’re serving Israeli food” and sometimes leaned toward saying “Middle Eastern food.” I felt particularly conflicted in talking to one of my closest and oldest friends, who is Palestinian, about it. How could I tell her that we have Israeli food at my wedding when she’s about to eat traditional Palestinian cuisine?

As I figure out my feelings about this while dipping chips into my Trader Joe’s Mediterranean Hummus (I’m going to get SO much Jewish guilt from Mom after this), I think where I am is this: I grew up with this food. I love this food. This food comforts me. I enjoy sharing it with friends so they can better know me. But I also acknowledge that words matter. Names matter. Origins matter. In a world that is reckoning with its various past (and ongoing) colonizations, let’s continue to share food with each other and experiment with fusing our foods together while celebrating and honoring the history and origins of where our favorite foods come from. I don’t need to call it “Israeli food” for it to be meaningful to me and comfort me. Or maybe it becomes Israeli specifically when your falafel comes with a schnitzel and a side of borekas. I think I’m still figuring that out for myself.

I definitely plan to make Mom’s hummus for my own children one day, but I’ll be sure they understand where it comes from so they don’t have to suffer from the same cultural indigestion. And there will definitely always be za’atar in the house to spice it with, but ideally bought from an Arab store and not from Trader Joe’s.

Arbel Bedak (he/him) is a gay Jewish-American music creative, business owner, and foodie. While food has never been a profession, it’s always been a love, and his love of cooking and experimenting in the kitchen comes from his mom’s affinity for the same. Arbel was born and raised in South San Francisco, CA except for three years where he lived on Kibbutz Kfar Hanassi in Israel, where he attended first, second, and third grades. He attended UC Davis where he was a devout band geek, marching baritone saxophone in the marching band and later directing the band for a year. He was also an active brother of Delta Lambda Phi Social Fraternity, which is how he met his bestie Mark Orr and, through him, our Nonna Chris. After graduating with a degree in music composition, Arbel moved to LA and began a career in music for media. In 2015, he met his amazing foodie husband Eric, and in 2021 they got married. After ten years working in the industry, Arbel opened Spectra Creative Agency in 2021 where he represents a diverse roster of score composers and music supervisors. Luckily, many of his clients are foodies as well, so lots of business happens over delicious meals!

Wow, you were so enraptured by Arbel’s writing that you made it all the way to the call to action! If you enjoyed this essay and want to support My Nonna Era, please share it on social media and tell your friends to subscribe.

Or how it’s supposed to be pronounced, “chummus” — you have to chhhh when you say it.

Did you chhhh when you read that?

Olde Brooklyn Bagel Shoppe on Vanderbilt Ave in Prospect Heights has a za'atar bagel that introduced me to the spice, def worth trying if you're close!